The Internet as a Novel Sociolinguistic Environment

Author: Corey Fleming︱Editor: Melissa Pradhan

About a year ago, I discovered the novels of Brandon Sanderson. To better engage with his work and see the plethora of fan-made content that is often only shared in private fan-controlled spaces, I joined a server, essentially a 100k+ member group chat, on the social media platform Discord. Months later, I followed a similar process with the works of Jorge Rivera-Herrans. Presently, having almost completed my undergraduate education in linguistics I looked back on these servers with a new perspective: these internet spaces display vast arrays of unique linguistic behaviour. This article seeks to introduce potential sociolinguists to the world of internet linguistics by outlining the nature of internet language and how said language is used. I will discuss how identity can be constructed on the internet and introduce some of the ways people communicate on the internet, while also examining the ways internet language is changing the way we speak offline.

Linguists suggest that identity is (at least partially) ‘discursively produced’ [2] and I believe this to be especially true on the internet as discourse is all there really is. On the internet, one does not immediately present factors such as age, gender, race unless they chose to. This allows for the curation and experimentation of digital identities. In their 2005 study, linguists Bucholtz & Hall interviewed a member of the Indian Hijras, a group that utilise feminine linguistic forms in order to separate themselves from their male birth sex [2]. This method of identity construction is easily applied to the digital world and removes the need to challenge the interlocutor's assumptions based on appearance. Furthermore, users possess the ability to create multiple accounts, usually for public and private displays, allowing users to grant differing degrees of access based on closeness. Hence language features such as obligatory gender marking can be explored freely. This allows people to communicate in a way that is true to them without having to worry about discrepancies between their physical appearance and linguistic expressions.Thus, users can create multiple identities to express themselves, depending on the account they are posting on. This theory builds on previous studies of audience design which suggest that when communicating to a large group, people must take into account the knowledge and assumptions of the people within the group [11]. The ability to create multiple identities allows people greater control over their interactions which leads to greater comfort in their discourse.

In the process of constructing their digital identities, internet users make use of communicative methods exclusive to the digital medium. The greatest example of this is Emoji, with 92% of the online population stating they use emojis [4]. Emoji, and other tools that will be discussed later, exist to circumvent the issues with the internet as a medium. In the case of emojis, they make up for not being able to see your interlocutor’s face over text which can affect the intended meaning of a message. Emojis therefore act as tone indicators that mimic the facial expressions or gestures that co-occur with in-person speech. [4]. However, most uses of emojis are contextual. While emojis can be used for gestures, they can also signify one’s membership to a fan-community [5], story-telling/pantomime [1], and to fill content gaps comparable to real world silences [7]. The variety of situations in which emoji can be used speak to the nuances and complexities of internet discourses and cultures.

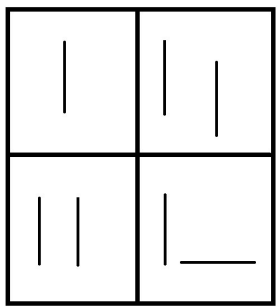

Other than emojis, another entirely novel method of internet communication is the meme. While memes are most often associated with humour, the use and history of memes can contain a vast degree of nuance. For example, examine the first image below known as the “Loss meme” [3], a comic strip from the internet webcomic Ctrl+Alt+Del. Then compare this to image 2, a later recreation of the meme accessed on the Tumblr blog of Lauralot89 [8].

Image 1. ‘Loss’ [3].

Image 2. ‘Loss.jpg’ [8].

Evidently, what began as a fully drawn webcomic devolved into its barest elements. Without prior context, image 2 is meaningless, hence LauraLot’s extensive history. Thus memes operate in a similar vein as other discourse markers such as slang or technical terms. In her book, ‘Because Internet’, Canadian linguist Grethen McCulloch discusses the memes she and her friends shared back in university. She writes: “I went back and tried to find one of these memes to give here as an example, and I couldn’t find a single one that wouldn’t require at least a full paragraph of context, but danged if they didn’t still make me laugh after all this time.” [9]. We see that one’s ability to understand these memes identifies them as internet users and communicates to those around them that they are, essentially, native speakers of the internet. Knowledge of the Loss meme communicates that you were on the internet during the era of this meme and its constant remastering.

The influence of internet language is not limited to digital spaces. A comedic example of this is Oxford University Press’s Word of the Year for 2024: “brain rot” [6]. Brain rot is a term used to negatively describe the influence of ‘low-quality online content’ on an individual's language use. This influence is characterised by phrases such as ‘sigma, Ohio, and skibidi’. This phrase saw a 230% increase in use between 2023-2024 [6]. Here we see the pervasive effect of the internet and digital spaces on the physical world. The internet creating trending ‘words’ or phrases is not a new phenomenon either as seen by the popularisation of ‘sus’ due to the video game Among Us [10].

The internet is a large, varied space that contains a wealth of unique linguistic characteristics that present interesting avenues for future study. McCulloch writes that “like the decentralised network of websites and machines that make up the internet itself, language is a network” [9]. Thus, to study modern language we must examine the internet in the same way historical linguists study the past.

References

[1] Benenson, F. (2010). Emoji Dick [Lulu.]. Retrieved September 11 2024, from https://www.emojidick.com/.

[2] Bucholtz, M., & Hall, K. (2005). Identity and interaction: A sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies, 7(4–5), 585–614.

[3] Buckley, T. (2008). Loss [Graphic]. Retrieved January 11 2025, from

https://cad-comic.com/comic/loss/.

[4] Gawne, L., & McCulloch, G. (2019). Emoji as Digital Gestures. Language@internet, 17(2), 1–19.

[5] Graham, S. L. (2019). A wink and a nod: The role of emojis in forming digital communities. Multilingua, 38(4), 377–400.

[6] Grathwohl, C. (2024). Oxford Word of the Year 2024. Oxford University Press. Retrieve January 22 2025, from https://corp.oup.com/word-of-the-year/.

[7] Danesi, M. (2019). Emoji and the expression of emotion in writing. In S. Pritzker, J. Fenigsen, & J. Wilce (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Language and Emotion (pp. 242–257). Routledge.

[8] LauraLot89. (2017). Can you please explain what loss.jpg is? Retrieved January 11 2025, from

https://www.tumblr.com/lauralot89/163080581251/can-you-please-explain-what-loss-jpg-is-ever y.

[9] McCulloch, G. (2020). Because internet: Understanding how language is changing. Vintage.

[10] Meriam-Webster. (n.d.). January 22 2025, from

https://www.merriam-webster.com/wordplay/what-does-sus-mean.

[11] Yoon, S. O., & Brown‐Schmidt, S. (2019). Audience Design in Multiparty Conversation. Cognitive Science, 43(8), e12774.